Bestiary |

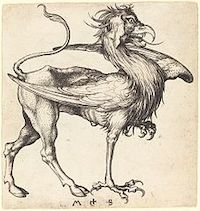

Griffin

By its appearance - usually a combination of eagle and lion - you can tell that this interesting monster comes from the Orient. Like its equally picturesque relatives, the mantichora is an example. The griffin was first introduced to Europe, of course Hellenistic, by Hesiodos, unfortunately we don't know the incriminated work, so the first author, extractible even in modern times, was Herodotus. He mentions one of the most popular and essential pieces of information, namely the affinity of griffins with gold.

Whether digging it out of the ground to make nests (and then, thanks to parental instincts, chasing after gold diggers) or guarding deposits of this precious metal, in any case this trait helped keep them in the popularity charts. In this case, they served the same function in the East as European dragons or gnomes.

Herodotus, describing the war of the griffins with the one-eyed Arimaspans, Aeschylus, and later Pliny were among the few ancient authors who left written accounts of the griffins. The creatures were much more successful in the visual arts, with numerous depictions of them surviving on virtually everything from abdication coins to armor decoration to sarcophagi.

The Middle Ages favored them, too. Griffins, like many monsters, have made their way into heraldic emblems, but they have also received official recognition. While dragons, manticores, centaurs and basilisks generally joined the army of darkness, the griffin took the other side. Although sometimes considered a demon, he was more often identified as a symbol of Christ. Certainly his monstrous combination contributed to this, for both the lion and the eagle are animals of royalty.

By the Middle Ages, then, there were also the first confusions common with mythological creatures today. Marco Polo - and he was not alone - heard the tale of the Ruchch in Madagascar, for example, and interpreted the griffin as its main character. And since the Czech term for the griffin is the Noh the bird, it is not difficult to see that later translators and storytellers of oriental tales also made the same confusion. Since the Ruchch is, however, an entirely different creature, I shall devote to it another, the following story.

Illustration by Martin Schongauer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

9.10.2024 (16.5.2004)

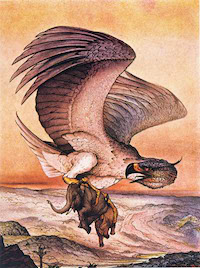

Roc (Ruchch)

is a common bird of somewhat larger size than the griffin. Usually a giant vulture or eagle. It flies in Arabian legends, but also in the legends of Madagascar and Malaya, so its area of operation is the Indian Ocean. You know him well from the adventures of Sinbad.

It is no problem for it to grasp an elephant in its claws, and it hunts them in this way, as Marco Polo reminds us. It simply grabs the elephant, carries it up and drops it on the ground. According to a Malay legend, (unfortunately told in confused and inaccurate children's books, so I'm on the fence about whether to believe it or not) sometimes the Ruchch eats up the city and feeds on the folk.

Unlike the griffin, however, the ruchch is closer to reality, and probably not exaggerating too much. Madagascar was mentioned, and you can guess where I'm going. To the Aepyornithes, the Madagascar ostrich, one of the largest birds ever to live on this planet.

Madagascar ostriches were certainly still alive at the time of the famous European and Arabian explorations, written about in the mid-seventeenth century by Etienne Flacourt and, after all, Marco Polo, adding to the otherwise herbivorous giants a taste for elephants (which probably came into legend under the influence of oriental stories) and the ability to fly. Other, smaller and more inconspicuous animals have also added to the colorful reputation, and if one has encountered a three-and-a-half meter huge bird, and if the animal - if it had the same habit of protecting its eggs as the recent ostriches - has run after it, then it is certainly not to be wondered at.

Illustration by Charles Maurice Detmold (1883-1908), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

9.10.2024 (16.5.2004)

Werewolf

Writing anything about werewolves is a bit of a challenge. You don't think so? On the one hand, one compound-complex sentence would be enough, on the other hand, a hundred-page paper wouldn't fix it. I don't want to do the former, I am not capable of the latter. But I'll do something: I'll take you to – let's call it the staircase of werewolf initiation. From that one sentence to the limit of the aforementioned study.

Enough talk, here we go.

Chapter One: Man turns into a wolf

A werewolf is a man metamorphosing into wolf form. Under the full moon, as the films reveal, for example, from the black and white beginning. Most of the time it's due to a curse or a bite from another werewolf. If vampires expanding their population in a similar way springs to mind, you're not too far off.

Turning into a wolf is also possible through knowledge of the relevant magical practices, as documented, for example, by a number of tales from my country. But not only from there. In the simplest case, you just need to drink from the water caught in the wolf's trail, for further transformations you don't need more than a somersault over a log. Anytime.

Chapter Two: The Monster

Where most modern (literary) werewolves are no different is in the inclination to the Dark Si... sorry, the Evil. Although good werewolves (fighting evil vampires, for example) have become a bit of a cliché, too. The old lycanthropes, especially those of the late Middle Ages and beyond, were indeed demons. For xenophobic reasons, and thanks to the Christian tradition that lumped almost all supernatural beings into that bag. With rare exceptions, all monsters belonged to the Devil's stable; supernatural abilities belonged only to God and the Devil, the former certainly did not waste them, and the latter had to be destroyed.

Against the strong pagan influences, medieval Christianity used something that we do not associate with that time today - rationality and, in a way, a materialistic understanding of the world. The behavioral formula was simple - unnatural things came from the Devil. The Middle Ages tried not to believe in witches and denied supernatural phenomena, with rare exceptions, passing them off as delusions and charms. It was only much later, when the old gods had really gone, that the supernatural dared to be adopted, living on in the surviving ruins of former beliefs and in the tales of the people. And only then did the first witches flare up.

What the officially sanctioned werewolf of the time looked like is revealed, for example, by the Bishop d'Auvergne of Paris. He describes a case in which the devil possessed a man, and made him believe that he was becoming a wolf and that in this form he was committing terrible sins. He carried him away to hidden places, but the man remained in his skin, only deeply asleep. The wolf form was, of course, the Satan himself.

The lycanthropes of later times adopted their ways from the devil, attacking cattle in wolf form, sucking milk from udders, scaring people, and suffocating them in their sleep. If you have some suspicion of other supernatural beings, then wait for the last chapter.

Chapter Three: the Curse

Even in the devil-obsessed Middle Ages, there were exceptions. According to older beliefs, the transformation of a man into a wolf was possible, so tales of victims of the curse have survived. An example from Brittany – the tale of the Bisclaveret.

The familiar motif of the discarded garment appears in this story. While the fairy tale swan princesses have to hide their feathered garments in order to remain in human form, the opposite was true for the Breton nobleman who turned into a wolf. When his not-so-honorable wife discovered that her husband was a werewolf, she asked where he hid his clothes before his metamorphosis and then stole them. The poor baron remained a wolf.

Fortunately, the story ends well – the wolf had infiltrated the king himself while hunting. Tame behaviour contrasted with attacks on the only person in the royal court (the unfaithful wife) revealed that this was no ordinary animal. The nobleman was given a dress and the adulteress a well-deserved punishment.

Chapter Four: The Skin-changer

Usually (not always) a werewolf was an evil demon. In pagan times, transformation into an animal was not a bad thing; even crowned heads took pride in it, especially among the southern and eastern Slavs. From the Slavs, in fact, Europe adopted the werewolf in its almost present form. (Voluntary metamorphosis is known elsewhere. And not only into a wolf.)

The wolf is, of course, a significant apotropaic animal. Revered and worshipped, in Bulgaria it was considered a good omen when it took a sheep, in French legend it saved the honor and life of a certain lady... For a long time, the other – the man in wolf's skin, or werewolf – was the evil one, but in the very beginning the transformation into a wolf was nothing bad or exceptional.

Back to the Slavs for a moment. They, as you already know, spread the belief in vampires to their neighbors. It didn't take much, and instead of flying transfusion stations, hairy monsters were running around at night, old legends were the same. Or mixed. We know the Serbo-Croatian tales of werewolves rising from the grave and attacking ladies and travelers. The origin of the species was similar: the werewolf used to be the fruit of strange unions of witches. A child, who is born feet first. The one conceived at a new moon could become a werewolf, too. Even a child endowed at birth with pre-milking teeth, which is another superstition later attributed to vampires. The transformation itself, as noted above, may have been a not too difficult gymnastic act, but sometimes metamorphosis was only possible on the solstice.

More bizarre are the later folklore tales where a man might transform during an unspecified incantation, with a stick tucked behind his belt to represent a wolf's tail. While I do not believe that this practice is a memory of any wolf mysteries, it is certain that the belief persisted.

If we take our binoculars for a moment and look into the jungles of East Asia, we can find lycanthropes there as well. Not in the form of wolves, of course, but tigers. This is understandable, given the aforementioned function of the wolf in European cultures.

Chapter Five: The Doppelganger

Here we come to the roots. Behind lycanthropy lies something truly ancient and worldwide - the belief in the Double. Indeed, a slight shake is all it takes to shake off a cursed man or demon and reveal the old superstitions. In its pure form, the above story by d'Aubergny shows that the Double, the soul of man, leaves the body mostly in sleep. It usually moves in the form of some animal, whether a wolf or a bear (or a tiger, as I recalled in the Asian look-back), and above all: everything the Double experiences is reflected back to the sleeping man. Not only does he see through the doppelganger's eyes, he also takes all the wounds that the doppelganger in animal form has taken, hence the farm boy in the Czech tale who, as a werewolf, rampaged through the woods and sheepfolds, lost an eye when the wolf was scratched by one of the dogs that ran on his trail.

Behind the werewolf, then, is a human soul enjoying a momentary independence. And here I'll stop, because, on the one hand, the topic would spill out of the cup, and on the other hand, I can refer you with a clear conscience to Claude Lecouteux's Witches, Werewolves and Fairies: Shapeshifters and Astral Doubles in the Middle Ages (Fées, Sorciéres et Loups-garous au Moyen Age, Historie du Double, 1992), which covers the whole topic in full and, above all, in a clever way.

The attack of the werewolf was recorded in an engraving in the sixteenth century by Johannes Geiler von Kaysersberg, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

14.11.2024 (23.5.2004)

Hecate

Three heads and three bodies give the Greek underworld goddess the right ancient mythical touch. Daughter of the Titans Perseus and Asteria, she was, as the legend still goes, in charge of monsters and phantoms, overseeing the field of witchcraft and roaming the graveyards at night in the company of a pack of fearsome phantom dogs. But that's not the whole truth.

Thanks to a shrewd choice of party in the Gigantes' rebellion, she was given considerable power by Zeus in return for merit (in fact, the new god had no choice but to leave the old goddess considerable power), both in heaven, on earth and below. Hence the seemingly dangerous person whom men feared and from whom they protected themselves with amulets and sacrifices of dogs, honey, and black sheep, can be found in the sky as the goddess of the moon. Yes, that was primarily Selene, but in certain circles, it belonged to Hecate. It would have been related to the witchcraft in which she was engaged, but our lady had, as has been said, power on earth, where she served as the goddess of childbirth and protector of the immature.

Nor did her depiction originally have an aura of terror and unnaturalness. The triple body was (supposedly) first sculpted in the second half of the fifth century BC by Alcamenes, and his work, which stands on the Acropolis near the Temple of Athena Nike, inspired others. The original depiction of Hecate had previously been a wise woman with a torch. And a single body. The image of the three quickly caught on, and was given an expanded version that said the bodies were lion, dog and mare.

Belief in Hekate had already degenerated in ancient times into protection from the dreaded underworld goddess. Pillar statues of Hecate served as a security measure, whether erected in homes, at city gates, or at crossroads. Apart from the aforementioned sacrifices, food was traditionally placed at these pillars on the last day of the month. It was believed, of course, that she consumed them herself; likewise, it was generally known that the poor people would provide the edible offerings.

From the underworld, she influenced human lives more substantially than one would think, for among her subjects were the nymphs Lampades, the Empúses, the demonesses she sent out to do harm in the world, and above all the Erinyes, the persecutors of the purveyors of evil deeds. Hecate herself was not malicious or evil. Nor could she be, given her true origins. And the real origin can be traced back to a twisted Greek myth.

She was a good friend of the goddess of the harvest, Demeter, whom she helped search for her lost daughter, Kore. She was kidnapped by Hecate's boss, the ruler of the underworld, Hades, to whom the underworld goddess was, of course, not loyal; together with Demeter, she forced Helios to reveal under interrogation that he had seen and covered up the whole kidnapping and that Zeus was covering up the crime as well. This resulted in Demeter's revenge on the whole world and Zeus' forced decision that Hades had to release Kore. Then, when Koré (as Persephone) had to stay in the underworld over the winter as a result of the trick, Hecate kept an eye on her and made sure Hades kept the covenant. This trio of goddesses leads to the union in the triple goddess, where Hekate was the name of the third form. All the more so because Hekate had moved into Greek myth from Asia Minor, from where highly noble divine ladies were constantly arriving in the Mediterranean to recall the old days of matriarchy with their existence. Cybele is a case in point.

The accompanying image is of a Roman statue (found in the Vatican Museum) depicting Hecate in her common triune form, source: Wikimedia Commons, licence public domain

6.12. 2024 (19.2.2011)

Trivia

Roman Trivia was the goddess of witchcraft, graveyards, and crossroads; probably due to the usual Roman literalism, she haunted real crossroads, although originally they were fateful crossroads. Thus, summed up in a single sentence, it would seem that she was merely the Roman counterpart of the Greek Hecate, which may be true on the one hand, but on the other may be hiding a domestic deity. But so perfectly that not much remains of it.

6.12. 2024 19.2.2011

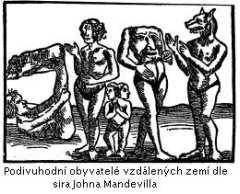

Monoculi, Monocoli, and Anthropophagi

Monoculi (Monocles) – in myths of course – were people equipped with only one unpaired visual organ, by the rules of axial symmetry placed in the middle of the forehead above the root of the nose. The most famous one-eyed people are, of course, the Greek Cyclopes, but this community deserves its own entry, so let's move on. I will wring some monocles out of the ancient literature after all; the monocles were unspecified far northeastern Arimaspians who have already been mentioned here in connection with griffins. According to Pliny the honest Arimaspians prevented the griffins from stealing gold, while Mr. Herodotus tells how the virtuous birds resisted the raids of the marauding Arimaspians on the gold deposits, the contents of which the griffins used to build their nests.

Though it may seem confusing at first glance, the Monocoli are not the Monoculi. In the picture, one can be found on the far left, resting in the shadow of its own single leg. Hence the name, the creatures called Monocoli are the same as the creatures called Sciapodae, the former meaning With one foot in Greek while the latter In the shadow of the foot. The first description of these interesting people is left to us by none other than Dr. Ctesias. It was then, too, that the information was verified for the next few hundred years, that in great sultry weather, these inhabitants of the tropics really hide themselves from the sunlight in the shadow of their own feet. Others later added to this the discovery of the surprisingly swift movement that their hopping on one foot allows.

The anthropophage is a man-eater, just as the bacteriophage is a bacterivore, and the sarcophage is a creature that does not discriminate between flesh types. That the first, second, and third can be found in natura on this planet needs no reminder. Although you need a microscope to see the latter and a paid trip to somewhere far away to see the former. But the Anthropophagi of myth are not just some honor-obsessed Papuan traditionalists. Nor is their food specialization their main hallmark. It's appearance. As you can glean from reading old English tales, these cannibals have no head. Fortunately, they have retained all the necessary organs, the eyes have moved to the shoulders, the mouth to the chest and the brain to places unspoken in polite company.

The British belief in Mandeville´s tales, and the legends that have been handed down in the Isles, is evidenced by a bit of real literature at the end.

Wherein of Antars vast, and Desarts idle,

Rough Quarries, Rocks, Hills, whose head touch heauen,

It was my hint to speake. Such was my Processe,

And of the Canibals that each others eate,

The Antropophague, and men whose heads

Grew beneath their shoulders. These things to heare,

Would Desdemona seriously incline...

– William Shakespeare. The Tragedie of Othello, the Moore of Venice

6.12. 2024 (1.6.2004)

Kappa

Kappa is a Japanese water demon. It looks like a turtle with a monkey face, drowns the two most endangered human categories in the legend - small children and travelers, and attacks animals, including horses. As you can see, it's no match for its central European cousin in terms of behavior. Neither in other characteristics - while the waterman from the South Bohemian pond has to keep his coat-tail wet all the time, his Shinto colleague keeps his long hair in the same condition. On the other hand, however, the kappa are very intelligent, and occasionally befriend a sage; that is the way mankind has acquired the art of divination from scattered bones.

6.12. 2024 (6.6.2004)

Wondjina

In the Dreamtime, these first inhabitants of the Australian continent hid in caves. Their self-portraits were left on their walls, which show that they looked just like us, only missing their mouths. One of the most famous members of this nation was a certain Walaganda, who climbed to the heavens and is credited with the creation of the Milky Way.

You don't see the Wondjinas anymore, but their spirits can be seen. They appear around the lakes.

6.6.2004

Yara-ma-yva-who

Small red men, not exceeding one hundred and twenty centimeters in height, with large heads and large mouths, lurk in the tops of Australian fig trees. As soon as someone appears under the tree, the little men simply drop down and grab their prey tightly. First, they suck blood. They eat the meat on the branches for dessert when they get back up on the branches.

6.12. 2024 (6.6.2004)

Morgawr

The Morgawr is the famous Cornish marine equivalent of the even more famous Scottish freshwater Nessie. It is a sea serpent between twenty and forty feet in length, with an eight-foot tail, scaly legs, and a beak-like head. It's said to look like a prehistoric lizard and... Here we go again. The aquatic monsters of Loch Ness and Labynkyr, the sauropod Mokele Mbembe, and others you can find and add to the cryptozoological literature.

The recent information is similar - lots of eyewitness sightings, some vague photographs, and indistinct video footage (in this case dating from 1999). Several eyewitnesses spotted the humpback sea monster in the 1970s, fishermen catch something here and there but don't haul in or bring it in, you know, I'm cautious in such cases.

But perhaps my skepticism will be disturbed, for a few weeks ago a cousin of mine sailed out of those parts into the Atlantic. I'll wait till he gets back and try to get some information out of him. Then I may return here with fresh information. There's one thing wrong with it, though - this relative of mine is very fond of making things up and exaggerating. Maybe I'll let it go.

16.12.2024 (27.6.2004)

Willy Wilcock

When I read the legend of Willy Wilcocks Hole, a cave near Polperro in Cornwall, I was reminded of a quote from Chesterton's short story The Sins of Prince Saradine:

“All right,” said Father Brown. “I never said it was always wrong to enter fairyland. I only said it was always dangerous.”

For Willy Wilcock the fisherman was one of the visitors to Faerie (for an explanation of this word and this phenomenon I recommend Tolkien's famous essay On Fairy-Stories), the Land of the Fairies, whence, like so many others, he found no way out. He is still looking for it, which is why on stormy nights his cries come from the cave.

16.12.2024 (27.6.2004)

Bolster

This giant once fell in love with St Agnes, back in the days when giants were a common Cornish population. He was a proper fellow who, when he straddled, had one foot on Carn Brae and the other six miles away. Nor did he disregard the reputation of his people, stealing cattle, threatening the neighborhood and those tiny creatures who tried to defend their flocks of sheep. He was just a nuisance.

But then he met Agnes. Surely a suitor with such a reputation would not have been a mainstay of early Christianity, and she wasn't. To prove his feelings, Bolster had, according to her wishes, filled the hole in the Chapelporth cliff with his own blood.

Of course, there was a ruse. The giant, for whom the few liters of blood would not pose a significant threat to his life, readily agreed. He had no idea that the designated hole was not a cave, but a hole running all the way through the cliff to the sea. And like the devil, grinning as he filled a sock with gold with the heel cut off, Bolster watched and watched as the blood drawn from his arm took no end, the level in the cave rising and rising until it drained completely and his soul walked away into the giant sky. The bloodstains on the cliffs at Chapel Porth are still sometimes seen today.

16.12.2024 (27.6.2004)

Vis

In New Britain, this creature is one of the most feared. From a demonological point of view, rightly so, because it is the local species of vampire. It flies around at night, scratching people's eyes out with its long claws.

16.12.2024 (5.7.2004)

Civatateo

Noblewomen who die in childbirth sometimes become vampires called Civatateo. Fortunately for us, this happens overseas in Mexico, and these ladies in question are of Aztec descent. They hide in temples, but their hunting grounds are the crossroads, where, as it happens, they lie in wait for travelers. They don't look very attractive, white as paper and wrinkled. Lest you mistake them for a resting, tired old woman and try to help them, they have a dead man's head drawn on their clothes or tattooed on their skin.

16.12.2024 (5.7.2004)

Guaxa

In today's short and quick overview of dangerous bloodsucking creatures, I can't leave out Europe. This time the Iberian Peninsula. From the north of Spain, I will complete the collection with the Guaxa, a witch of the classic appearance, wrinkled, with a single tooth and the behavior of a vampire. She's after young blood, choosing her victims from children and lambs.

16.12.2024 (5.7.2004)

Crâsnicul

The offspring of a woman and a demon, a child with the features of a piglet. It is active soon after birth, running around the house and screaming. He is said to desire to kill everyone in the house and then return to hell. Or so they say in Romania, where the creature is believed.

16.12.2024 (13.7.2014)

Marţolea

Tuesday's demon. It's in his name too, Marț Sara, as he is sometimes called in Romania, means Tuesday night. On this day and part of it, women should not bake bread, mow, sieve, or do laundry, which is why Martolea came into the world.

Unless he's looking for guilty women, he's at home in the mountains. It is not known what he looks like on his days off, but he works in many different shapes and forms. Most often in the body of a goat with a horned but otherwise human head. He also appears in disguise as an old crone (a model for intercourse with married women), as a handsome young man (intended for unmarried girls), or as a fair maiden (suitable when meeting men). However, he does not work with the last group of people; as already mentioned, he focuses only on women. And when he catches them breaking the working peace, he punishes them cruelly: the unmarried ones he dismembers and scatters their intestines on the walls, for the married ones he attacks children and husbands outside the home.

16.12.2024 (13.7.2014)

Joimârița

An ideological relative of the previous Tuesday's watchman. Operates in parts of Romania, but not on Tuesday, on Thursday. She too carries the calendar in his name, in Romanian this day is called joi (and has its origin in the Latin Jovis dies, the day of Jupiter).

A woman with a big ugly head and messy hair (originally, of course, the pagan god of death) targets lazy children. And young ladies, whom she revisits once a year, on Maundy Thursday. If they show signs of laziness, he punishes them.

16.12.2024 (13.7.2014)