Bestiary |

Minotaur

Mínótauros is one of the most famous monsters of Greek mythology. Despite the fact that he didn't live very long, he didn't drive more than thirty people out of the world and didn't even guard the treasures. But so it goes. He became entangled in the stories of two great men of the Mediterranean, Zeus' son Minos and Poseidon's descendant Theseus.

That name, Mínótauros, of course, means Minos' bull, and Mínós, the ruler in Crete, is certainly a more interesting character, whose curriculum vitae and curriculum post mortem will be revealed some other time since his afterlife career in the realm of Hades makes him an adept for membership in our collection. But to the point.

The monster inhabiting the Labyrinth was half man and half bull, and for a simple reason:

Well weigh'd Pasiphae, when she prefer'd

A bull to thee, more brutish than the herd.

is reproached in Ovid's Metamorphoses by a certain Scylla, who is not the monstrous Scylla you can read about here. For Mínós's wife, Pasiphaë did indeed went off the rails with the white bull which the king refused to sacrifice to Poseidon. She solved her lust with the help of the famous engineer Daedalus. He made a wooden cow, covered it with real leather, attached wheels, and dragged the model out to pasture. Pasifaé climbed in, and the bull, grazing nearby, soon did as his instinct commanded.

The result of this union was a man with a bull's head. His real name, as may be seen from the title, was Asterios or Asterion. This name appears several times in the Mínós myth, and while the "bull of Mínós" Mínótauros is a later designation from the time when the affair became public and Asterión was already disposing of victims in the Labyrinth, the "Celestial" or "Star" Asterios represents the bull in its original mythic function, i.e. as the animal of the Moon Goddess.

Daedalus, living in Cretan exile at the time, entered the story a second time when he built the fabled Labyrinth at the request of a cheated husband. Mínós locked Pasiphaë and Asterius in it, while the sacred bull-father went mad in the meantime. He became dangerous, attacking people. Hérákles took him away from Crete and released him on the Argean plain, but things were not much better on the mainland. By the time Theseus destroyed him, the bull had killed hundreds of people, including Minos's son Androgeus.

Which doesn't quite add up.

Androgéos was apparently murdered in Athens at the behest of an ardent fan of the local athletes, King Aigeus of Athens, or the home team wouldn't have won. And this unsportsmanlike behavior upset Minos. He wielded enormous naval power at the time, so it was no problem for him to force his former allies in the Seven against Thebes to make regular sacrifices.

Every nine years the seven Athenian boys and girls would be thrown to Minotaur (suddenly the king found the monster convenient). There is also a variant of nine young men and women after seven years and a version that acknowledges this sacrifice annually, but the former is both more familiar and more mythologically comprehensible.

The ship with the black sail set sail twice before the third draw saw the entry of Theseus, the great hero of Greek myth, now forgotten in the shadow of Heracles and Perseus. Also, two young men, disguised as ladies to make the squad stronger, but there was no need for that.

Thanks to the treachery of Minos' daughter Ariadne and her now-famous ball, Theseus penetrated the center of the Labyrinth and killed Minotaur. With what, there was already controversy at the time. Whether it was the sword, Théseus' fabled club, or just his bare hands, in any case, Asterion left the story, the hero climbed out safely and thumbed the nose at the king.

He took the amorous Ariadne with him, just in case, to forget her - like Iásón Médeia - on the island of Naxos. Though it is said that the god Dionysos claimed her.

The Cretan version of this semi-historical legend does not include Minotaur; according to it, Theseus clashed with the Minos general Tauros, even with the secret permission of the king, because Tauros made Minos cuckold. The Labyrinth was said to be a well-guarded prison. There is a Cyprus story too, and it is downright political.

But if the more realistic versions were to take hold, we would lose one rather interesting monster and therefore this Bestiary entry.

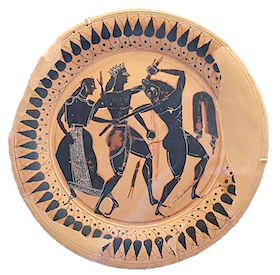

Plate painted by Lydos. Struggle between Theseus and the Minotaur presumably in the presence of Ariadne, 550--540 BC, Yair-haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

18.12. 2024 (13.6.2004)

Krivapeta

A solitary species making its home in caves, ravines, or near mountain streams. A wild woman with long green hair, dressed in white. With feet backward, heel first. Quite a common sign of supernatural forest creatures, and not only Slavic ones. However, it was Slavic settlers who brought Krivapeta to the inhabitants of Italy's Natisone Valley, a region on the border with Slovenia.

A well-known herbalist, able to predict the future. Sometimes dangerous, sometimes willing to advise, especially with the running of the farm (which reveals the true age of this being, in its original form it could have belonged to the Teachers and therefore, since we are in the south of the Slavic settlement, to the Vilas). She sometimes took a reward for her advice - the children she fed on - which brings us to the last phase and the last piece of information, both to the readers here and to the once Natisonian immature: if you think of playing in such dangerous places as valleys with steep slopes, the proximity of treacherous water or caves, beware of her.

Illustration by Samuele Madini, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

13.1.2025 (24.7.2022)

Elementary beings

Already the ancient Romans – oops, the wrong peninsula again – already the ancient Greeks assumed that matter consists of four elements, namely fire, earth, water, and air. They were not alone in this, in distant India it looked similar, the four elements Agni - fire (sometimes replaced by Tejas, heat), Ap - water, Prithvi - earth, Vâyu - air, but sometimes supplemented by ākāsha – space, and vijñāna - consciousness, such a six were then called the primordial elements.

In both these cases, of course, it was a fairly decent philosophical idea, based on the scientific knowledge of the time. Later times, however, brought supernatural beings into the picture. Here are these inhabitants of the elements, mainly from the point of view of the famous medieval physician Paracelsus:

Earth

The spirits of the mountains and the earth are usually called Gnomes. It is believed that this name was coined by Paracelsus. However, as even he admits, we can – and many people do, of course – call them Pygmies. Through what we consider a solid and impenetrable substance (and how impenetrable when one stumbles and the road warmly hugs him!), that is to say, through rocks, they cheerfully pass to and fro, which does not prevent them from building dwellings-sometimes people find them; they are unhigh vaulted rooms with trampled floors. Gnomes can see through the ground and don't need air because they breathe - minerals, of course. What they eat is uncertain, but I know for certain that, like the creatures that follow, they do not drink water, for thirst is only natural to humans.

Gnomes look as you might imagine - two spans tall elves, wealthy, guarding both treasures and deposits of precious metals. They probably have their own economy because they mint coins, but since they like to give them to humans, it won't be too bad with the underground market. They don't like the sun and prefer to flee from it back into the stone.

Paracelsus also tells us that the gnomes and the others dress themselves, which wouldn't be so interesting if he didn't mention the origin of the basic raw material of the local clothing industry:

"For it is possible for God to create not only the sheep which are known to us, but also the same in fire, in water, in the earth.“

In all cases, they must be really interesting animals.

Air

Paracelsus' name for the creatures of the air is Sylphs. But there is no reason not to call them Sylvestri.

They are, in a way, the closest to us because they breathe air. They are also more rude and unkind than other creatures. This is not the sarcastic observation of a wise man, but a characteristic belonging to all beings of the air; while men have not often met with gnomes, and, owing to their philanthropy, have been quite happy to do so, they have always been in contact with airy beings; wind, storm, and hail have taught the peoples of the whole world to be on guard in this case.

Because of their ancient mythological origins, Sylvesters also had many forms, but the one in the illustration is the work of the nineteenth-century painter Edward Fellowes Prynne and is understandably highly romanticized.

Water

Call them what you want, like Undines, Paracelsus says of the water demons. And he writes of Nymphs, a relic of ancient heritage. As in the case of the Sylphs, the influence of the deep past is more than evident.

Although the water beings are of both sexes, most of the legends speak of water ladies, mentioning instances of their marriages to humans, which the Undines (in their desire for their own souls, for this is the only way elemental beings can obtain souls) often enter into. Paracelsus recalls the story of Melusine, as well as a number of similar European legends. The offspring of such a union are of course descended from the father.

According to the author of the Elementary Beings, the Undines include the Sirens and the Sea Monks; there was, as can be seen, an attempt to categorize all supernatural creatures. Therefore, both Slavic Vilas and Rusalki as well as Mediterranean Naiads can be included among the Undines. And, of course, similar creatures from Germany or France.

Even Undines guard treasures. Those in the deep, of course.

Fire

While their amphibious namesakes are found near water, for the mythological Salamanders we must travel to a liquid of a completely different composition. The Salamanders, creatures of fire, live in volcanoes, which is why they are also sometimes called Vulcans. They are long, lean, and thin and breathe fire. Paracelsus considers the Sicilian Etna to be their residence, but it is usually supposed that they live in any fire.

Like the Gnomes, the Salamanders know the hidden present and future, so an intimate friendship with one of these creatures may not be out of the question. Sometimes they give up their monster shape as a fire dragon and may appear in human form. Similarly, the strange lights hopping around the meadow can be identified as them.

Fire is the essence of their bodies; da Vinci remarks that the Salamanders feed on fire, while Pliny, on the other hand, as an authority much older than the gentlemen so far mentioned, informs us that the creature is so cold that their touch will extinguish the fire. This is connected with the synthesis of the lower mythological beings mentioned; in the case of the Salamanders, of course, a similar conversion took place as in the case of Paracelsus' Undines; the Phoenix did not later turn into a fire elemental just for its fame, the salamander group of Paracelsus' time certainly includes Pliny's Pyrota, a winged quadruped living in the Cypriot smelting furnaces. If it leaves the fire and rises into the air, it dies after a while.

Which, in conclusion, adds another creature to our collection.

Sylphs by Edward Arthur Fellowes Prynne (1854-1921) [Public domain]

23.1.2025 (11.7.2004)

The Flying Dutchman

Let me first set the record straight about a commonly perceived inaccuracy. The Flying Dutchman, which is often perceived as a haunted ship, is the name given to its captain. The ship is innocent.

One more time: A haunted ship you meet in the North Atlantic, for example, is not the Flying Dutchman. Because... Wait, a third introduction.

Of course, there are plenty of haunted ships. I have several records in my archives - for example, of the Neptune, which sank off the Cornish coast. As well as the ghost of the ship, a light belonging to the lantern of a passenger on another ill-fated vessel looking for her drowned child can be seen on the shore at St Ives; the Rotterdam appears in Cumbria in the north of England with ghosts calling for rescue; the Betsy Jane appears at Whitehaven pier on the anniversary of her wreck. Not to mention the waters around the Isle of Wight. Haunted ships are simply part of European seaside and maritime legends.

The Flying Dutchman's ship is, of course, the most famous. Why, I don't know, and it doesn't really matter. It's quite possible that there's a really strong story behind the ghost.

One of the stories, of course. There are several variations of how the reputation has engulfed some of the weaker legends and how it has evolved over time. The basis is, of course, common. That is - apart from the shipwreck - also the place where it occurred. Which brings me back to the second introduction.

The Flying Dutchman is an inhabitant of the southern hemisphere. There is a version set in the North Sea in which Captain von Falkenberg wanders in its waves, having sacrificed his soul to the devil, but this is probably an echo of one of the stories that the Flying Dutchman has assimilated. His own legend, however, begins in 1641 (1680, 1729), when a certain Dutch ship belonging to the East India Company sailed off the South African coast. She was returning from Asia and had only to round the Cape of Good Hope on her way home. Although the weather was not good.

This part is common to all versions. The cape ahead and the clouds overhead. As well as the stubbornness of the captain, who could have been named Vanderdecken, Van Demien, Van Straaten or also Van der Decken (or Van Fill-What-You-Want, as one of my sources notes).

"By all the sea creatures, we'll circumnavigate that cape, even if it takes until Judgment Day," he let it be heard.

According to the mildest version, the ship crashed into the shore in a storm, but God heard the captain's curse. And from then on, in the storms off the Cape of Good Hope, until the end of the world...

A more dramatic and readerly tale tells of a mad, alcohol-soaked sea dog who, with a pipe in his teeth, drove his ship around the cape. The passengers begged him on their knees, the crew as one man demanded a change of course and a return to port, but the captain would not allow it. The waves crashed over the deck, the wind tore the sails and broke the yards, it was no use.

You know the saying, "By all the sea creatures..." and so on. Eventually, everyone on board pulled together and committed to what, in an era without trade unions and Amnesty International, was tantamount to mass suicide - mutiny. The captain, freshly fortified by another cork of beer, approached the collective bargaining with a clear argument - he pulled out a gun and shot the rebel leader. And threw him overboard.

But just as the dead body touched the surface, a shadowy figure appeared on deck.

"You're a very stubborn man, Captain," she tried at first in a good-natured way, but Van Yak-just-named pointed the gun.

"I didn't ask you any questions. Get lost, or you'll be next."

Which Shadow didn't. The captain pulled the trigger, but the gun went off in his hand, and moreover, he learned that he would be sailing with a crew of ghosts off the South African coast for the rest of eternity, on a haunted ship, never docking, and bringing death to all who saw him.

He still does this - according to all versions of the legend - to this day.

It's not so hot sometimes with the ban on entering ports; according to a milder version of the legend, every seven years the captain is allowed to land and search for the woman whose pure love would deliver him from the curse. Even the inevitable doom is not so inevitable to the casual observer; there would be no observers (and they are, even in this day and age); the story goes that two beings, Good and Evil, play for the captain's soul, and depending on which has the upper hand at the moment, the real ship sailing by will be saved or not.

I have already alluded to the North Sea's contribution to miscellaneous here, so before we close, I will recall the lyrical variation for tender souls, according to which the captain suffers forever for unhappy love.

But I like the original version more, after all.

5.2.2025 (18.7.2004)

Homen marinho

Translated from Portuguese, they are simply the Mermen.The Jesuit Fernao Cardi and Gabriel Soares da Silva, the owner of a sugar mill, have left us warning messages about the Homen marinho, found in the Caribbean Sea. The tall men, appearing in summer, near fresh water, lured passers-by with their voices (read the modus operandi of a related creature from a nearby continent, the Ahuizotl, or something about Sirens). The poor victims were strangled and squashed, after which the surroundings were treated to a strange moaning sound. And they fled.

At other times, they would take their prey to the larder; later, the bodies found were stripped of eyes, nose, fingertips, and genitals. It is suspected that crabs and fish picked up these particular delicacies on the drowned sailors because the sites are easily accessible, but why spoil the spookyology with common natural history. After all, if that's what you're after, an animal - the aquatic mammal manatee - was probably behind the creation of these mermen.

5.2.2025 (25.7.2004)

Nansaveset and Lionemeylan

A notorious sibling pair of sea demons in Micronesia. Nansaveset, nestled on the southern shore of Ponape Atoll, for example, is a tall, dark-skinned man who spreads an unpleasant odor around. He has taken up residence in the mangroves and from there he watches for his victims. In plain European terms, this demon is an incubus, a sex demon, always eager to seduce any girl within reach. Although, as has already been said, he does not smell very appealing, he succeeds in his work, aided by magic. He hides the bait in the half of a crab, the tempting delicacy, set on the way, is usually picked up by a passing lady, cooked, and consumed, the feast resulting in an unquenchable desire for Nansavet. And the journey to the south of Ponape.

When the demon tires of sexual play with the woman in question, he releases her. But the victim takes away gonorrhea as a souvenir. Nansaveset's sister Lionemeylan gives the same venereal disease to her partners, providing the same demonic services to the male population of Ponape. But she has competition, another female demon, a succubus named Lumotelan. In what way Lumotelan attracts men I do not know, but I have information that in the middle of the act of love the demoness disappears, which, apart from the probable disillusionment, brings a certain madness.

5.2.2025 (25.7.2004)

Větřice

Although it flies in the air and has wind in its name, Vetřice is not quite the demon of this element. This creature, represented by the whirlwind and drafts, causes toothaches, earaches, swelling of the face and carries disease.

Elsewhere in Bohemia, however, the wind whirlwind is a bogeyman of a different category altogether. When a man sleeps, his soul sometimes crawls out to stretch... and we're back to the eternal problem of the Double. The folktale about a knife thrown into a wind vortex, that stabbed into the an innkeeper at a nearby inn is not just a fanciful story, but proves the ancient belief that any harm inflicted on the Double is transferred to humans. As you can see in the story of the Nordic Doppelgangers.

5.2.2025 (1.8.2004)

Mařebyla

The daughter of the lord of Sonnenberg, a castle near Chomutov in Northern Bohemia, once lost her groom and from that unhappy love, she became a forest demon. Well, I took the story a bit short, but it has several versions and who knows how it really was. She didn't want to join a convent so she ran off into the woods? Or was her beloved beheaded by a nobleman from nearby Deer Mountain? In any case, the forest spirit Mařebyla appears in the woods around Výsluní with a tin glove on her left hand, luring food from the woodcutters and caressing them.

5.2.2025 (1.8.2004)

Charlotte de Breze

In the beginning there was a classic, almost operettaish scene. The husband returned home early and unannounced, causing a triple shock. Jacques de Breze, however, acted like a nobleman and immediately banished the unfaithful wife Charlotte and her lover from the world. He then sold his French chateau, Brissac - if you wanted to visit it, you had to go to the Loire Valley, the proverbial nesting place of chateaus of all kinds - and sold it. Charlotte started haunting it. It's lasted to this day.

5.2.2025 (8.8.2004)

Albert Liddy

The fabled Phantom of the Paris Opera has a number of cousins. In addition to my favorite Phantom of the Operetta (who was a material character and worked in the pages of Eduard Fiker's wonderful humorous work), there is also the New Zealand Phantom of the Wellington Opera to be found. In 1913, the builder Albert Liddy became him.

The reason why he committed suicide and why he started haunting is also age-old - criticism of his work. He couldn't take it and then made sure it didn't pay off after his death. Anyone in the building who disparaged it could be sure that something nasty would happen to him. During the directorship of Pat Shields, who retired in 1990, he said this happened three times. Each time in the same place. So watch your mouth when you visit the Wellington Opera House.

5.2.2025 (8.8.2004)

Ušatý Radouš

At first glance, this is a common inhabitant of old castles, namely the ghost of one of the former owners. Radouš, sometimes also Raden or Roden, already belongs to the Czech castle Radyně by name. He is also its founder, as well as founder of nearby Pilsen.

But the situation is not so simple. Behind the goatee, pointed teeth and long ears, there is a much older being, coming from the darkness of pagan antiquity. He may have once meant the same thing to the Pilsen region as Rýbrcoul did to the Giant Mountains. Later, he degraded into a mere ghost, who met his fate through a not very honorable Bluebeard life; the ugly Radouš, son of a quarreling landowner couple, went into the woods, built Radyně with the help of goblins and murdered his wives because they bore him equally unsightly sons. The seventh one escaped and survived, Radouš disappeared and began to haunt the ruins of the castle with a wheel of pitch.

Folklore has it that if Radouš and his cargo turn up at noon, a storm will come. But in older records, he is not only to be found in Radyně, but also in Pilsen and its surroundings. One of the great collectors of legends, Václav Krolmus, writes about him as a former pagan god of the Pilsen region, as a personification of the natural powers. But everything has been forgotten, and Ušatý Radouš remains only in the legend of Radyně.

He is not alone in the castle, however; he is said to have once been responsible for the curse of a certain uncouth Moor, and now he is kept company by Černý Hanuš (Black Hanus), who rides a wheelbarrow at midnight (when he can be seen) and at noon (when he is invisible) along the battlements of Radyně. He is, however, a silent companion, not that he does not want to talk, but he is only allowed by the curse to shout, "Buy, buy pitch."

The black dog that guards the Radyně's treasures doesn't seem to talk much either, so in the end Radouš really didn't win.

15.2.2025 (15.8.2004)

Green Man

His face appears all over the world nowadays, but you can see it most often when you take a sightseeing tour of English temples. Like the French Gargoyle, this man has entered architecture, and his face, under a mask of leaves, adorns many churches. Whether he's called Green Man, Green Jack, Jack-in-the-Green, Old Man in the Woods, or Green George, he's always the same creature, an old pre-Christian vegetation deity who has degraded over time into a folkloric figure. But a respectable figure, no scarecrow.

His career as a pagan god is ancient, some hints of his existence can be found in Altamirano rock drawings. He appeared in Europe as early as the ancient Stone Age and outlasted all imports of Celtic, Roman, and Germanic deities, which is not unusual for such an archetypal figure. Its immigrant relatives bore the same attributes, of course, we are talking about the natural cycle of Spring-Summer-Winter, or Birth-Life-Death, and again and again. He also became one of the essential elements of the Robin Hood legend and is considered a likely candidate for the Green Knight of the famous literary work about Sir Gawain.

This good spirit of the forest, known throughout Europe, simply could not be ignored. Hence the protector of the trees, usually covered from head to toe with leaves, most often oak, has survived in English folk festivals to welcome spring and has taken up residence, as already mentioned, in the sacred decoration of local churches. It is not uninteresting that (according to Mike Harding) a significant number of churches with Greenman decorations are dedicated to the Virgin Mary, for this saint has taken over the functions of many pagan goddesses, especially in the Islands. Indeed, even Robin Hood's aforementioned Merry Men were originally Marry'Men. Like the Morris Dancers, who also belong to the welcoming of Spring and the Green Man... but that's treading on untrodden ground I don't know my way out of yet.

15.2.2025 (5.9.2004)

Jenny Greenteeth and Peg Powler

Although the color in the name of today's next visitor suggests at first glance a kinship with the aforementioned woodsman, the Jenny of the Green Teeth is a demon of another element altogether. She lives in a Yorkshire river and is a nasty water hag, drowning people.

Her relative from the River Tees is Peg Powler, a water demoness of equally unpleasant appearance: green-skinned possessor of sharp teeth, who behaves in the same way as most water demons – drowning and drowning until she drowns.

15.2.2025 (5.9.2004)